We often get the question “As I get older, my portfolio needs to become more conservative, right?” Our answer is always, “It depends on what you’re trying to do.” Becoming overly conservative can be a huge mistake. We’ll get to that in a second.

However, the reason this rule of thumb** exists is that, as you approach retirement, you begin a major financial transition – shifting from SAVING money to WITHDRAWING money. The logic is that you should start “locking things in” (so to speak) so that your spending isn’t much impacted by market fluctuations. The concept is important, and it isn’t conceptually wrong at all.

Many retirees struggle with the emotional side of this saving-to-spending shift, especially after saving for 30ish years. It’s human nature, and we understand that.

Of course, what we’re all trying to avoid is FINANCIAL RUIN. We don’t care as much about having more dollars, we just don’t want to run out of money!!!! However, it is important to understand that over decades, more conservative portfolios generally lead to having less money, which equates to less spending, and can bring on long-term risks, too.

Before I dig a bit deeper, I want to discuss the “cobra effect”. This story goes back to colonial India. It’s a neat reminder that incentives matter. Here’s the short version:

- Delhi had a cobra problem (yes, venomous snakes)

- To eliminate the snakes officials decided to pay residents a bounty for bringing in dead cobras

- More cobras started to appear (people started breeding them to make money)

There was a problem, action was taken to solve that problem, and that made the problem worse. Talk about your all-time backfires (movie quote!).

This is the key lesson from the cobra effect, so I’m going to restate it: By taking action to solve a problem, you can actually make the problem worse. Think about someone so fearful of a car accident that they merge onto the highway at 35 miles an hour when all the other cars are going 70 – it’s risky business!

Back to building retirement portfolios. It is VERY possible that someone who is:

- Afraid of financial ruin

- Takes action to prevent running out of money

- Runs out of money BECAUSE of that action

For the case of this post, I’m going to talk about that action being TOO conservative with a portfolio, out of fear of running out of money (though there are other actions that could fall into this category). And I’m going to use the 1965 retiree as my example (as in, retiring December 31, 1965).

Why 1965? Well, it turns out that it’s the worst year in the post WWII era to have retired with a basic U.S. portfolio (other countries have had different experiences, to be sure). This person, in hindsight, had every right to be fearful. Here’s why…

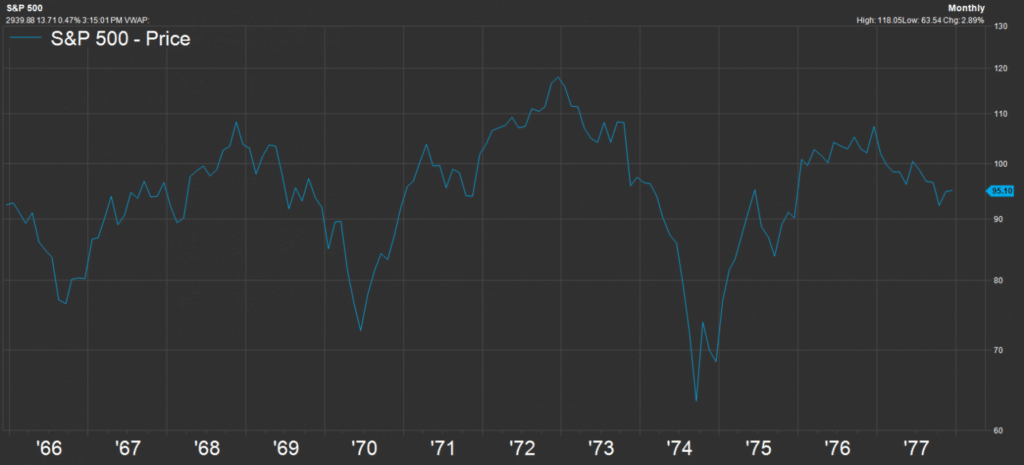

From 1965 to 1980 – the first 15 years of our case study’s retirement – stock AND bond markets stunk. Here’s a chart of the S&P 500’s price from the start of ’65 to the end of ’77. It’s flat overall, but with three noticeable drops in that period, including the big one in ’73-’74. Ouch. Very unlucky.

At least dividends helped U.S. stocks still earn nearly 4% per year through that period. Bond markets were about the same, earning just over 4% per year (without fees). That might not sound bad.

But it gets much worse. The cost of living rose, on average, a little over 7% per year from the end of 1965 through 1981. How could our retiree keep up? Those years were ROUGH – high volatility, poor returns, and high cost of living adjustments.

And that’s what everyone fears–that the proverbial “stuff” hits the fan at the very moment they retire. Bad luck. Really bad. Imagine the emotional roller coaster that our 1965 retiree would have ridden. Could he/she have stuck with a plan through that volatile time? (knowing it wasn’t just volatile in the markets).

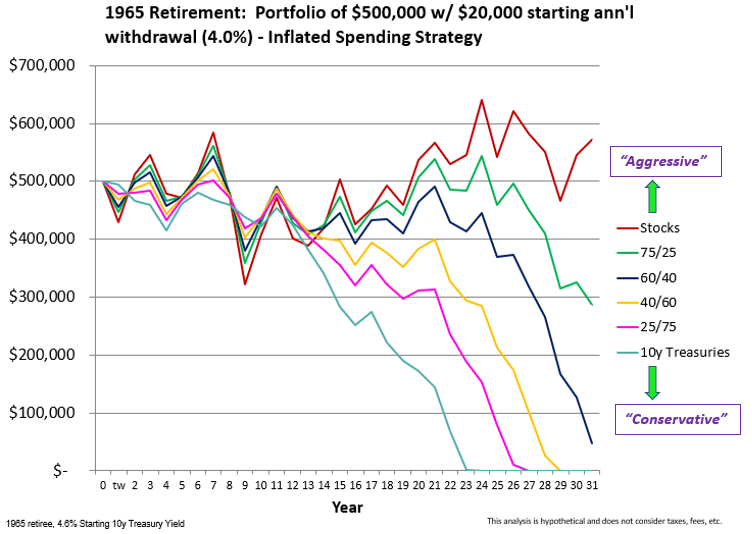

Now, here’s where knowing about the cobra effect can be helpful. Let’s say you’re about to retire, and you’re afraid of running out of money. So out of that fear, you build an ULTRA CONSERVATIVE portfolio (or worse, you buy an expensive annuity that doesn’t match your goals). How well do you think conservativism worked, for a retiree with the worst luck, retiring in 1965?

It so happens that 1965 is far enough back that we know what happened, so we can look at that. You might be surprised to learn that an ultra-conservative portfolio failed because the rising cost of living ate it up after 22 years. What’s more – after 15 years, 70% of the original money was gone, leaving not much money left in case of a major healthcare issue, or some other big late life expense. Our retiree can’t get that money back; it’s gone.

Let’s look at this visually. What I’ve done below is charted six simple portfolios our 1965 retiree could have held, from very “conservative” (10-year U.S. treasuries) to very “aggressive” (all U.S. stocks). With all studies, we need assumptions. Here are mine*:

- 4% starting withdrawal rate (while I’m showing starting with $500k, the starting value is not relevant – only the 4% is relevant)

- Our retiree wants to maintain her/his lifestyle as prices rise (in other words, spend more to buy the same things as they go up in price)

You’ll notice that the most conservative portfolios would have run out of money within 30 years. For our unlucky 1965 retiree, the more stock, the better the long-term outcome. That’s even though at the end the big drop in 1974 the most aggressive portfolio was, at that time, doing the worst of all the portfolios shown below. It dropped to nearly $300,000 from the original balance of $500,000 – which might be really hard to stomach, but as long as our retiree does not panic, works out great.

It’s important to highlight – I’m not saying that retirees should just go all-in on stocks and ignore conservative holdings inside their portfolio. Most people just don’t have the stomach or discipline needed to handle living off of money that way. For one, it’s really hard to cut back on spending in down years. Additionally, we haven’t talked about the unfortunate 1928 retiree, but we might in a future post (suffice it to say an all-stock portfolio if you need spending money doesn’t seem to be the world’s greatest idea).

Another important thing to point out in this theoretical exercise is that there’s nothing keeping somebody from making changes along the way – say buying more stock when stock markets are down. However, who would really be able to put more stock in their portfolios when times are really bad? Our experience says not many – it takes a stomach of steel, which most don’t have.

But what I’ve shown here is that it is absolutely possible to be so fearful, so conservative, that the very thing an investor is afraid of (running out of money), can happen BECAUSE a portfolio becomes too conservative. Going “in the bunker” with your portfolio might FEEL like it’s the right thing to do, but it can be very dangerous in the long run.

The portfolios, withdrawal rates, and returns shown in this post are theoretical. They do not consider the impact of fees, taxes, or other complexities involved in personal investing. Nonetheless, we think the concepts illustrated can be instructive.

*For this exercise, I used the S&P 500 and U.S. 10-year treasury total returns, found on Aswath Damodaran’s website here: https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.stern.nyu.edu%2F~adamodar%2Fpc%2Fdatasets%2FhistretSP.xls

**In the past decade, retirement research has updated this old rule of thumb to something more useful. Wade Pfau and Michael Kitces have written extensively on the topic, and if you really want to go in the weeds, read all about it here (it’s academic).

Jacobson & Schmitt Advisors, LLC (“JSA”) is a registered investment advisor. Advisory services are only offered to clients or prospective clients where JSA and its representatives are properly licensed or exempt from licensure. The information provided is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice and it should not be relied on as such. It should not be considered a solicitation to buy or an offer to sell a security.